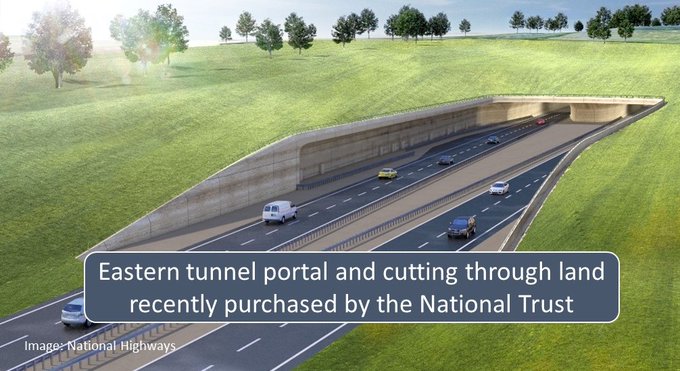

Proposed Stonehenge tunnel, with portal within UNESCO designated World Heritage Site. (National Highways image.)

Suppose you had a problem on or around your property. A leaking roof, an awkward neighbour, a noisy road.

And someone with clout, the council perhaps, came along and said it had a scheme – at no cost to you – to make life better. Considerably better. After checking that the few obvious snags wouldn’t bother you too much, at least in your lifetime, you would probably welcome it.

And this way of thinking is the only explanation I have for the National Trust’s support for the government’s proposed £2bn A303 tunnel and dual carriageway at Stonehenge.

The trust manages 827 hectares (2,100 acres) of downland surrounding the famous stone circle, within the Stonehenge World Heritage Site (WHS). The two portals for the proposed tunnel would sit inside the World Heritage Site boundary, causing “substantial harm” to its significance, according to the government’s independent examiners. The eastern portal and cutting would be on land bought by National Trust in 2020, and within the WHS.

UNESCO, which designated the WHS, said in 2020: “The proposed tunnel length remains inadequate to protect the OUV (outstanding universal value) of the property…a longer tunnel section… is required in order to avoid highly adverse and irreversible impact on OUV, particularly on the integrity of the property.”

Yet at its AGM on November 5th (2022), the trust is calling on its members to reject a motion asking it to reconsider its support for the government scheme.

I’m trying to understand why the trust thinks the current scheme is such a good idea, and why many members are likely to agree, and vote against the motion. (If members don’t vote, the chairman casts their votes as in favour of the trust’s line.)

At a stroke the proposed tunnel would do away with the busy road, which passes within 200 yards of the circle. Tranquillity restored. Traffic underground for 3.3 km. Not a vehicle to be seen from the stones, for the first time in 120 years or so.

The long-standing Stonehenge problem solved, at last. Never again will the world’s most important and recognisable prehistoric site be blighted by noisy, polluting vehicles. This is the vision the trust wants its members to vote for in Bath (or online by October 28th). And, to those unfamiliar with the fuller picture, it must seem compelling.

In its position statement to members in the agenda, the trust doesn’t spare the buzzwords.”Traffic-clogged A303…severely damages the World Heritage site”; “an obstacle to exploring the site”; “current situation cannot continue”; “evidence-based”.

Put simply, the government says a longer tunnel, with portals outside the WHS boundary, is too expensive. And an above-ground bypass to the south, again outside the WHS, is impractical.

But there is another course of action. Inaction. The present road has enabled huge numbers to see the stones, as they pass, usually at a respectful crawl, on this busy stretch. Who knows what inspiration has been given to young minds by the awesome sight?

But continuing to let passers-by behold the wonder of the stones, desirable as it might be, is not, of itself, a strong enough reason for inaction. There are better arguments for not improving the road, and leave an internationally important site unscathed.

What revolutionary changes, only dimly perceived, might be made to the way we will travel later in the century and beyond? I live close to the Grand Union Canal, a major highway at the end of the 1700s and in the early 1800s. Then, around 1836, Stephenson drove his London to Birmingham railway through the tranquil fields near my home. In little over 100 years the canal lost all economic relevance and sank into the drowsy recreational waterway it is today.

I doubt if the canal’s promoters in the 1780s could have foreseen how it would be superseded so decisively by, at the time, unimaginable technology; just as, in the 1880s, companies providing fodder for cart horses were oblivious to the motorcar arriving, at speed, around the very next corner.

There will be more transport revolutions. Who can foresee the shape of private, public, and freight transport 100 years from now? The advance of autonomous cars could mean a higher carrying capacity on existing roads, with more vehicles moving safely in the some road space.

Other transport improvements between London and the Home Counties to the SW might include high speed rail links and capacity increases on existing lines, and silent, safe and clean air traffic, including airships. It’s possible that 200 years from now the road and tunnel will be redundant. The 4600 year old stone circle could last for another four millennia, but the adjoining land, for a scheme useful for a tiny timespan, will have been irredeemably damaged. It might be possible to fill in the tunnel and tear up the road, but prehistoric land scarcely disturbed, except by light ploughing, would be beyond restoration. The damage to the integrity of the WHS could never be reversed.

There is a daring precedent for inaction only 150 miles away. There are similarities between Stonehenge and the proposed bypass to the congested M4 at Newport with a six lane relief motorway.

The Stonehenge tunnel is principally designed to unlock traffic queues and cut journey times to and from the West Country. Taking traffic out of eyeshot of the stones is a subsidiary purpose.

The M4 relief road in Wales was promoted to solve chronic traffic congestion around the two lanes each way Brynglas Tunnels at Newport, on the principal road into Wales. In pure traffic-flow terms, its case was stronger than Stonehenge. Yet despite winning the backing of the independent inspector, the scheme was rejected in 2019 by the Welsh Government’s First Minister Mark Drakeford. And, in part, for a reason that does not apply in England.

In 2015 the Welsh parliament passed the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act. Unique to Wales, it requires public bodies to consider the long-term impact of their decisions. Sophie Howe, the first Future Generations Commissioner, was a prominent opponent of the M4 relief road.

Ms Howe had urged ministers to think of “shiny new 21st century public transport projects” instead of a new road. Her views are thought to have played a part in influencing the First Minister’s decision.

In England, however, the Westminster government has no obligation to consider the consequences of the Stonehenge tunnel for future generations. (It could be argued that the proposal in its current form could have a negative impact on the appreciation and enjoyment of the stones for hundreds of years to come.)

In Wales opponents of the M4 relief road made two main points. One was the likely damage to a precious wildlife area, the Gwent Levels, through which the new road would run. The second was that the road would attract and create more traffic, encouraging people to make journeys they might not otherwise have made, and generate more CO2 emissions. (This is ‘induced’ traffic; it refers to people driving further and more often because of new roads; transport experts have seen this happen since World War 2.)

The South East Wales Transport Commission was set up to look at alternative solutions to the problem of congestion on the M4 in Newport. It’s too early to judge the success of measures which have not yet been fully implemented. But as yet the ruling Labour party in Wales has not paid a penalty at the polls. There appears to be no going back on its decision to ditch the road.