In October 1920 Agatha Christie introduced Hercule Poirot in her novel, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles”. And the great detective lives on, in Kenneth Branagh’s adaptation of Death on the Nile, which follows the actor/director’s Murder on the Orient Express. The film is expected to open late in 2020.

1994 I interviewed David Suchet on set during the filming of one of the ITV Poirot series. This is a version of the article I wrote for Radio Times.

—————

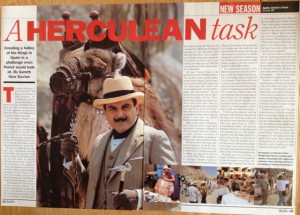

“The dust, Hastings. It gets everywhere.” His face set a grimace of deep irritation, the world’s most fastidious detective flicks the grains from his immaculate three piece suit with a brush he carries for such urgencies, as a hot wind down the Valley of the Kings whips up another smothering cloud.

All the dapper Belgian’s torments are assembled in one place – a searing sun, maddeningly agile flies and Hercule Poirot’s bane. Camels. When he was last in these parts, investigating several deaths on the Nile, the fussy sleuth had a set-to with an especially aggravating dromedary. Now he is convinced that the word is out among that beast’s many friends and relations – get Poirot.

So why is he back? Let the man who must understand Poirot better than any other living person explain. David Suchet, starting his fifth series as Agatha Christie’s idiosyncratic creation in The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, has sought to cool in a tent, where he reclines, a chamois leather steeped in eau de Cologne on his brow. He extends a grey-gloved right hand and greets me in the Brussels accent he retains between scenes, as he stays in character.

“Poirot hates it all,” David Suchet affirms, waving a battery fan. “Given the choice, he would sunbathe from indoors in London. But he returns out of curiosity. And for the challenge.” Archaeologists have been dying like flies in and around the 3000 year old burial chamber of the Egyptian king Men-Her-Ra. Even such a pathological fugitive from the sun and its discomforts as Poirot can’t resist finding out what goes on. Will his moustache wilt before the murderer is unmasked?

At least Poirot choose to be groomed as if for Pall Mall, sartorially parfait in suit, gloves, spats, patent leather shoes, cravat, tropical hat and all his little elegances – the pince-nez, fob watch and silver-topped cane, “to fend off the dogs, and the camels”. David Suchet has no choice but to suffer for his art under a 33° sun. “First there is the suit, then the waistcoat, then a thick linen shirt, and six inches of padding, then you get to me. Hercule Poirot must never perspire. My secret is to move as little as possible between takes and, on the advice I took from the Royal Marines, to pant like a dog.”

There is one small consolation. Hot it may be, but it could have been even hotter – we’re not in Egypt. A call from outside fixes our country of work: “Acción. Levantar el cadáver”. The extras are being ordered to bear away another victim.

We are one of the most productive outposts of the European Union’s filmmaking industry, Tierra Del Cine, 20 miles north of Almeria in southern Spain. At a director’s whim, it could be the Wild West, Arabia or, for two days, Christie’s Valley of the Kings. It’s more accessible than Egypt, the climate and geography are similar, and the locals are old hands at the film game: David Lean shot scenes for Lawrence of Arabia alongside a parched riverbed close by, and Sergio Leone set those high plains ringing with the sound of gunfire in the Dollars films.

For production designer Tim Hutchinson, it was a matter of driving around for a week until he spotted, in this tight valley, a setting fit for a Ramses. Then it was all down to photo references of the archaeologists Caernarvon and Carter at the tomb of Tutankhamen in the 1920s. Tim would have liked to have his cast walking under the great legs of Abu Simbel, but the budget only ran to a half-buried entrance of a tomb, and a pillar, erected, I was assured, by a working party of Spanish prisoners inside on crimes of passion.

A filming trip abroad must be planned with precision. Because of the high cost of hiring locally, all the props were acquired at home. The ruins were made at LWT’s Twickenham studio, the tents in Bradford. Poirot’s vintage Renault was brought out on a low loader, together with the other period vehicles, hired from a collection in Windsor. Only the animals are local: the camels, directly descended from those Lean used in his film, have been shampooed to look their best in their Poirot-threatening role.

Nothing was left to chance. A supply of fuller’s earth was packed in case the weather turned wet – perforated bags hanging from the car in which Hastings drives Poirot to the dig would create clouds of dust. There was a minor metrological conspiracy only the week before: it rained for two days and the desert burst into bloom. There was nothing for it but to ruthlessly root out every last flower. Wind is the other fear. “These old tents are like kites,” explains Tim Hutchinson. “If you don’t pin them down, they will fly over the next mountain.”

For an hour there is silence on set. Nothing concentrates the mind in Tierra Del Cine more than lunch, supplied in vast quantities by a mobile canteen, said to be one of the best in Spain. Replete, the crew drift slowly back in a range of headgear – from knotted handkerchiefs to designer sun hats.

Suchet returns to work after maintenance to the most important prop of the show, his twirly-whirly moustache – “the finest in London”. Made from yak’s hair, its integrity in this heat is crucial, and it receives constant attention from the make-up department. Poirot, Suchet has no doubt, would’ve been waxing it at every opportunity.

Tomorrow it’s all over. The caravan moves on, to briefly commandeer a mountain village for some street scenes. Gone with the wind, but not without trace. David Lean had left behind some palm trees. Agatha Christie’s brief association with southern Spain would be marked by an altogether more British memento. Under the savage sun it will stand until it falls apart: the wooden shed where the “archaeologists” stored the finds from the tomb. As English is a prep school cricket pavilion.