“There are many different ways to interpret the two words that have touched so many aspects of human culture. So many people know what they mean in Latin, and yet don’t apply them often enough in their everyday lives.”

This is the time for good intentions, clean slates, things to do purposefully listed, firm resolution. Keep it up at least for the few weeks of January, we persuade ourselves, and maybe the momentum of self-improvement will carry us through to a better us, our personal course more firmly charted than last year.

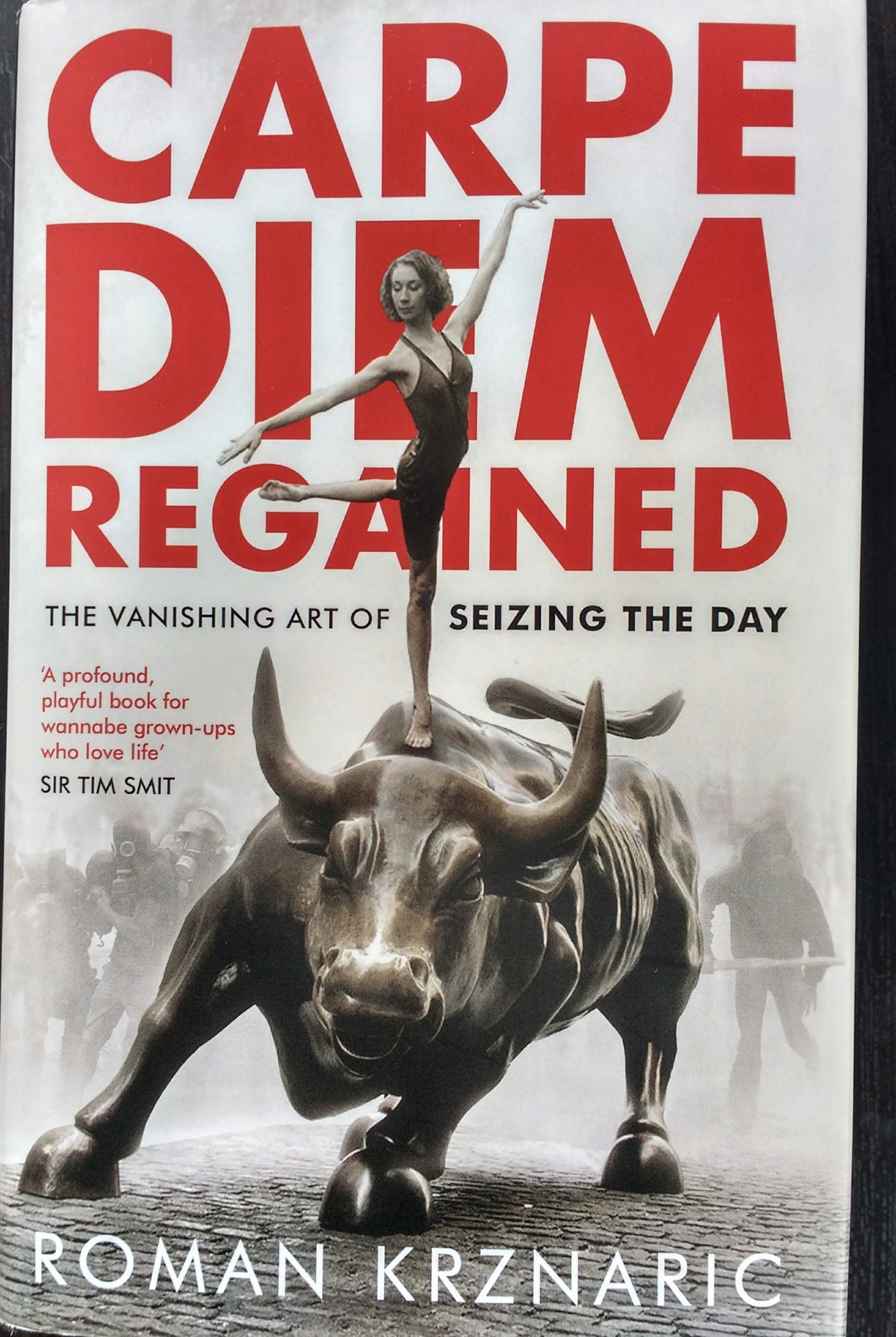

Searching my shelves for a guiding text, I came upon Carpe Diem Regained, by philosopher Roman Krznaric. (He kindly sent me the book after I tweeted my regret at missing him at the Hay Festival – I went to John Julius Norwich instead, which turned out to have been the right decision: it was John Julius’s last appearance there before his death in 2018.)

So was there ever such enduring promise invested in two such short words, culled from Horace’s Ode XI? “Even as we speak, envious time flies past. Harvest the day [Carpe diem] and leave as little as possible for tomorrow.”

Many people take the injunction literally: “Don’t procrastinate, just do it.” Had I followed that advice, you might have been reading this review a whole six weeks earlier (or ignoring it just the same).

There’s so much diligent, and wide ranging research in this book. Krznaric reports that out of all the mentions of the phrase in The Times, back to the 19th century, three quarters of the usages have the meaning I have just given.

No film handles this reading of seizing the day, and the moment, better than the Robin Williams movie Dead Poets Society. It’s a simple call to action. You are young, questing and full of potential. Use it, now.

But other, less noble, more self-interested, meanings are possible, he says. Could carpe diem just mean “enjoy” the day? Maybe it was only old Horace trying to seduce a young girl, before “envious time” changed her. Or did he simply mean: “be spontaneous”. Our ordered, timetabled life is too controlling. Let’s go back to the Middle Ages, when life was one long party (when it wasn’t fear and misery and grinding labour).

There’s another possible meaning. Was Horace’s intention that we should seize the moment in the political sense, as in, “let’s just have the revolution now”. Never was the time more right, it seems, than the day the Berlin Wall came down. Although this wasn’t a spontaneous event after all, the writer suggests. It was the end point of an opposition movement going back 10 years, here and elsewhere.

While this is a book about embracing life, and making the most of it, Krznaric doesn’t dodge death, at least as a motivator for seizing the day. He explores our curious attitude to dying, and our not seeing it as a daily possibility, a prospect therefore to inspire us to work hard at carpe diem. Most cultures do the same, however, evading the Grim Reaper’s gaze, despite the ever-present prospect of planetary wipeout.

But what if we treated every day as our first, not our last? There’s another example in the movies, this time in Richard Curtis’s About Time (2013), where a young man gets the chance to relive past days. Isn’t Curtis saying we should be seizing days, however unremarkable their contents, just for themselves?

Already you get the idea that Carpe Diem isn’t as simple as it sounds. We can spend hours just seizing its real meaning.

In other chapters Krznaric explores how Horace’s words have been manipulated – “hijacked”. First, by its enemies. Puritan asceticism in the 16th and 17th century determined to cut out “spontaneous enjoyment of life and all it had to offer.” Then industrialisation started to regiment things in the interests of big business: timekeeping was, and largely still is, all. One legal time management system logs employees’ time in six minute chunks to make sure they get maximum return from clients. Naturally it is called Carpe Diem.

There’s another possible corruption: carpe diem as – “just buy it”. 7 billion of us tap into our phones to try to find the reward of something we like. But are we making real life choices? Krznaric wonders if, rather than the freedom to buy, the credit card and the computer just gives us the chance to choose between brands.

I would argue that there are still genuine life-fulfilling experiences to be grasped at the touch of a key. I came within 5 hours of missing a Prom concert after it had been available on BBC iPlayer for 28 days, just by repeatedly putting off listening to something I could have accessed anywhere. It enhanced my day.

Something carpe diem is certainly not about is routinely switching on the TV for the national average of three hours watching a day, with another 20% of waking time given over to all that Internet and surfing stuff. That brings watching a screen up to a roughly 50% of our waking hours. Not much seizing the day as the way into (and yes there are some good programmes on) our daily dose of mindless passivity.

Krznaric has a statistic on how watching TV actually shortens our life (carpe diem in reverse?), even if we are watching sport, instead, presuably, of doing sport. (The research came from the British Journal of Sports Medicine). So here are our daily lives being hijacked, and we hardly even notice. So switch off, break the TV habit and – other recreations are available – learn the ukulele.

(A personal observation. Have you, like me, returned from a longish TV-free holiday and wondered if – and it is possible – now is the time to do without that siren screen for the long term, even if it means missing Bake Off?)

The writer talks about people making cape diem-inspired choices – “have the potential to take our lives in a new direction.” He gives us the lady who reinvented herself as nightclub dancer; the Holocaust survivor who thereafter lived life to the fullest; the photographer Don McCullin, who captured fleeting moments, from violence to love, mainly in wars, while in great danger himself. There is the lady who reinvented herself after going on a life assessment course at the age of 62 – it included her doing the fire-walk seven times.

Life life to the full, by all means. But, Krznaric cautions, it isn’t so easy for us to follow Richard Branson and skim around the globe in a hot air balloon. We have families to raise, mortgages to pay, student debt to pay off. So maybe “seizing the day” opportunities for most of us should be more modest, such as getting things right in our personal relationships, or pressing forward some cause or campaign we support. Because something else carpe diem means is keeping regret out of the day; we have the choice – just take it.

What about the hedonistic interpretation of carpe diem? Essentially our cultural programming has kept the brakes on for the past 2000 years. The prevailing attitude, although perhaps not so much in our own times, seems to be: no pleasure please (whether it be the delights of the bedroom, or the Caribbean cruise) – we must be responsible, citizens governed by moderation and self-control.

There is nothing wrong with sex, Krznaric argues. It is normally free, and it is carbon-free and a way to challenge consumer society – “sex remains one of the most important realms of life “for exploring and expressing the freedom and equality that society has to offer.”

What about drugs? (He sampled Amsterdam’s “coffee shop” wares in his research.) Certainly beware the dangers of drug abuse, but “let’s not rule out a chance of returning, if only occasionally, to the ecstasy of our childhood, whirling on the grass.” He does think there’s an argument for mind-altering stimulants, which can be such a powerful catalyst for social change. Hedonism has a place in our lives, as long as we don’t take it too far (like Elvis).

Carpe diem is acquiring fresh meaning. A new, narrower, interpretation for the phrase has emerged since around 2000. It’s about grasping fleeting opportunities, being immersed in the present. Living that timeless instant when we are unencumbered by memories of the past or thoughts of the future. And this usage was virtually non-existent before the 1990s.

This all come from the mindfulness movement, says Krznaric. But he is not so sure. There is collateral damage. We end up focusing too much on the moment, and the self. Surely thinking ahead is good for us? We know how fulfilling it is to pursue meaningful future goals.

He thinks mindfulness is crowding out other important approaches to carpe diem. Thinking about the past and the future is natural for a healthy mind; our brains are not so good at focussing simply on the present. We need the past, we need the present, and the future.

There is a case for reading carpe diem as spontaneity. Although perhaps not in the instant gratification sense of going to your phone to download that film, now, or book a holiday.

Some countries do spontaneity very well – Spain and Brazil for example. It is a way of breaking away from the tyranny of the deadline and the diary. Try it yourselves, Krznaric prompts. Experiment by blocking off Sunday afternoons, for example, for something off-diary. Try experimental travelling; jump on a random bus; draw a love heart on a map and walk its route

Then there are the crooks and the conmen who opportunistically seize the day to turn a dollar. This is the selfish side of carpe diem. Enjoy and enrich yourself, and never mind the harm, annoyance or inconvenience you cause to others – what Sadie Smith describes as a “flattening of the human personality”.

There are lots of right ways to be inspired by Carpe Diem, and just a few wrong ones, such as when you or your actions harm and upset other people. That’s one thing it shouldn’t be, a selfish doctrine. That’s carpe diem with a social conscience. Don’t limit other people’s choices.

Carpe diem can be a primary route to human happiness, the life of a deep well-being. But it should sit alongside other approaches. Ultimately it’s all to do with individual choice; it is not what we choose but that we choose.

The writer concludes that it’s still a powerful philosophy despite all the electronic distractions. He has been inspired to do new things, even if they are rather modest, and he has Horace to thank for it. (Although I disagree with him when he says you can spend too much time reading Patrick Leigh Fermor’s biography. This was the ultimate day seizer in the travel sense, who must inspired so many to put on their walking boots and “just go there”.)

Recently I applied carpe diem at its most basic level. I took a simple walk I enjoy doing, when I could have gone straight home instead. I decided to walk along the South Bank in the late summer sunshine. No personal benefit, no cultural stimulus, no retail therapy: simply a stroll along with several thousand other people. The bustle, the blue sky and the river. I just did it. Nothing happen, yet I’ll probably recall the day for years to come.

There are many different ways to interpret the two words that have touched “so many aspects of human culture”. So many people know what they mean in Latin, and yet don’t apply them often enough in their everyday lives. This entertaining, stimulating and even inspirational book helps concentrate the mind, move us to great deeds if we want, or helps us focus on simply making the most of life.

In my youth the self-help books used to be about making friends, learning languages and amassing a fortune. Seizing the day helps you do all those things. or none of them. You may not learn a single word of French, or earn a single cent today, but even if you can only look back on it at bedtime as as a day well lived, surely that’s enough?

Carpe Diem Regained The Vanishing Art of Seizing the Day

£14.99

Book reviews:

Also by me:

Free our best friend – time to walk the dog out of pedigree status?