When The Story of Holly and Ivy was first published, it was set in the Buckinghamshire market town of Aylesbury.

In later editions the location was switched to somewhere called Appleton. (There is a village of Appleton in Oxfordshire, but the descriptions in the book don’t fit it.) Has the book lost something as a result?

“And where does your grandmother live?” asks a gentleman in the train compartment.

“In Aylesbury”, answers Ivy.

“Yes, that will be two or three stations”, says the nice lady sitting opposite.

“Then there is an Aylesbury”, says the little orphan girl on her hopeful but uncertain way to her big Christmas Eve adventure. In The Story of Holly and Ivy she volunteers the name of the “pleasant and clean country town” in Buckinghamshire, “with cobbled streets going up and down”, as the place where her fictitious grandmother lives. “Perhaps she had heard it somewhere.”

This warmhearted Christmas fantasy by Rumer Godden has been a perennial seasonal favourite, on both sides of the Atlantic, since it was published in 1958. It tells the converging stories of a little doll (Holly) in a toy shop in the market town, and the girl (Ivy) who invents a grandmother there in a bid to avoid being sent to an infants’ home when her orphanage closes for the festive season.

And, remarkably, 60 years on, the old part of Aylesbury, 35 miles north west of London, hasn’t changed so much in its core atmospheric details.

“Houses with gables overhanging the pavements”; “the market square, where the Christmas market was going on”; the houses up around St Mary’s church, still “cosy…with their lighted windows.”

There is one big change, however. This very real place was written out in subsequent reprints and replaced with a bland, anonymous – and non-existent – town called Appleton. (The story stays exactly the same, apart from that geographical revision.)

I have been unable to find out exactly when the one word change was made. The book, with the original 1950s illustrations by Adrienne Adams, was out in paperback when we bought it in the late 1980s, and the town was still Aylesbury. (It is still Aylesbury in the Wikipedia entry on the book.)

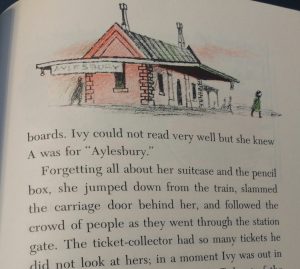

Our intrepid little adventurer makes a stab at the station name as the train pulls in. “A..b..y… Ivy could not read very well, but she knew A was for Aylesbury.” To leave us in no doubt, Adams includes a drawing of the old railway station, among several views in streets in the Old Town. Subsequently restored, it looks just the same today.

Our intrepid little adventurer makes a stab at the station name as the train pulls in. “A..b..y… Ivy could not read very well, but she knew A was for Aylesbury.” To leave us in no doubt, Adams includes a drawing of the old railway station, among several views in streets in the Old Town. Subsequently restored, it looks just the same today.

Some time in the 1990s, when the book was republished with illustrations by Barbara Cooney, (the British Puffin edition is illustrated by Sheila Bewley), the town’s name was changed, presumably with the author’s consent, or even under her direction. (Rumer Godden died in 1998).

If Godden did direct the alteration, then she must have had good reason for doing so. She lived nearby for a short time in three different addresses around Speen, 10 miles from Aylesbury, and would almost certainly have known and visited the town. Was she persuaded to turn it into anonymous “Anytown”, perhaps for the American market – the book is very popular there? The Boston Parents Paper named the book one of their “100 Best Children’s Books of All Time”. The Horn Book Magazine, the oldest of the magazines in the United States dedicated to reviewing children’s literature, felt it was “texturally rich and evocatively wintry” and recommended it as a read for the “whole family”. In the UK, The Guardian marked it as one of its “perennial favourites”.

But if that were the reason, why would, say, American readers be any more likely to relate to a town called Appleton than they would to a place called Aylesbury? – they might assume both to be invented.

Appleton isn’t a vaguely presentable composite of Buckinghamshire market towns. Aylesbury is Aylesbury in the Adrienne Adams illustrations. Go armed with the an early printing of the book, and you can still find those mainly Georgian, with some Tudor and Jacobean, buildings today.

It has to be Temple Street where Ivy presses her nose up against the toy shop windows. There are still one or two specialist shops in this historic street, even if today estate agent is the default business. You can easily picture the girl wandering up and down Castle Street, Church Street and Parson’s Fee around St Mary’s Church, and in the historic cobbled Market Square, where she sees the Christmas market.

There is ample compensation for Aylesbury and Buckinghamshire losing a starring role in the children’s literary pantheon. The excellent Buckinghamshire County Museum is a big draw in Church Street, with the Roald Dahl Children’s Gallery added on to it in the 1990s.

And relocating the story to Appleton should not spoil the innocent reader’s enjoyment of a delightful story. After all, books work on the reader’s imagination. The skilled storyteller should be able to conjure up a convincing and gripping made-up place out of thin air. Visual prompts from an illustrator are an optional extra. It is the image in the reader’s mind that matters.

Dylan Thomas set the lyrical A Child’s Christmas in Wales in some snowy unnamed seaside location. If you know Swansea, where Dylan lived until he was 20, you cannot fail to place it around the area on the west side of the city where he lived, on a steep hill running down to the sea. But by not naming the city he doesn’t detract from the power of the book. Nobody asks for that “missing” detail of exact location to be added to make it perfect.

Yet the point about The Story of Holly and Ivy is that the location was there in the first place. It was well chosen, with the toy shop in the (real) old town only a short walk from the (real) railway station, making it easy for a six-year-old girl to find. The sense of place is important, just as it is, admittedly in a different league of literature, when Jane Austen makes several references to real places in her books, most notably Bath, where she lived, in Northanger Abbey and Persuasion

She named them, presumably, because they served a vital purpose in the books. And so did Aylesbury Old Town in Holly and Ivy. Turning it into Anytown Appleton, for me at least, takes away just a little bit of the magic.