Exit from Shepherd Market onto Curzon St, where Patrick Leigh Fermor hailed a cab to begin his epic journey to Constantinople

Did one of the finest British travel writers of the 20th century start his epic adventure across Europe on a meteorological fib?

Patrick Leigh Fermor – “a thousand glistening umbrellas tilted over a thousand bowler hats in Piccadilly”.

The Sunday Times – “At Kew it was 33° (1°C). Light falls of snow again occurred locally.”

But does it even matter that it wasn’t pouring when he left ? Still winter afternoons don’t offer the descriptive writer much to go on, and made-up deluge and tempest were just right for his dramatic opening.

——————–

The man regarded as one of the finest British travel writers of the past century set off from London 88 years ago today on his epic hike across Europe.

Patrick Leigh Fermor chronicled his passage through pre-war towns and cities of a darkening Europe in late 1933, just as fascism was taking hold in Germany, in two wonderful, lyrical books, A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986).

Rereading the brief opening section in which Paddy, as he was generally known, describes his hasty departure from London to catch the overnight steamer to Holland, I was struck by the drama of this briefest of cameos, only one and a half pages, in which he describes his taxi trip on a rainy afternoon in the capital. Under such a biblical deluge, who wouldn’t want to be on their way to somewhere else, in search of (somewhat drier) adventure?

Aquaplaning

Except that it probably didn’t even rain in London that day. Paddy seems to have made up that extreme metrological detail to enliven his opening. And it is a splendid thing that he did. What could have been a prosaic crawl through London traffic turned into an epic adventure in aquaplaning through sodden streets.”We splashed up Ludgate Hill…the tyres slewed away from the drowning cathedral.” A tribute, incidentally, to the skill of the London cabbie in pre-radial tyres days.

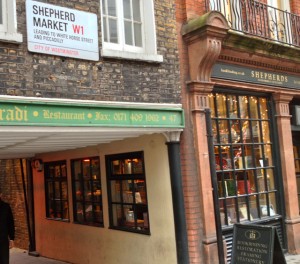

Paddy is helpfully precise with his dates. He sailed from London on December 9, 1933, aboard the Stadthouder Willem, leaving his lodgings in Shepherd Market in the West End and taking a taxi with three friends to embark from Irongate Wharf next to Tower Bridge. Next morning, in the early winter light, he set off on foot from Rotterdam to walk across Holland.

I’d always been puzzled at what seemed to be a very sudden change in the weather. Clearly Holland was snowbound. He refers to skaters on the canals, so the cold snap must have set in a few days earlier. Generally cold anticyclonic weather in near-Europe extends across to, at least, East and South East England. So why was it raining so heavily in London?

One possible explanation was that it had been cold, but that the weather was breaking, with a depression, bringing warmer, wetter air coming in from the west. That makes sense, but it’s not supported by the newspapers from that weekend, 8th to 10th December, 1933.

More out of curiosity than with a desire to question the honesty of one of my heroes – and besides, Paddy was looking back a long way when he wrote the book (in the 1950s) and it’s likely he did experience such dreadful weather in London streets at some time – I looked up those newspapers.

A thousand glistening umbrellas

Far from a continuous downpour where he sees “a thousand glistening umbrellas tilted over a thousand bowler hats in Piccadilly” and “The clubmen of Pall Mall, with china tea and anchovy toast in mind, scuttling for sanctuary up the steps of their clubs”, his trip to the boat probably took place on a crisp, frosty afternoon. It would have been quite dry, unless there was a snow shower, which might have added some dramatic detail, but not the sort he was looking for.

Instead of forecasting heavy rain, The Times of Saturday, December 9, departure day, promised a mainly dry weekend, apart from scattered showers of sleet or snow over England.

The centre of a large anticyclone had moved from Scandinavia to Scotland. There was “a drift of intensely cold air from Eastern Europe.” Temperatures were well below the seasonal average.

The first snow of the winter fell in central London the previous day (December 8). The AA was advising motorists “contemplating journeys to carry skid chains as frost has been forecast.”

Forecasts weren’t as precise in the 1930s as they are today, but it’s hard to see how the temperature could have risen suddenly enough for there to have been a deluge over the Strand, as he describes – “our taxi, delayed by a horde of Charing Cross commuters reeling and stampeding under a cloudburst.” A blizzard would have been more likely.

Looking back on the day, The Sunday Times (December 10) reported that “As far west as Plymouth the temperature in the early afternoon [December 9] was only 31° (0°C)”. At Kew it was 33° (1°C). Light falls of snow again occurred locally.” And that is just the sort the weather he described, quite accurately it would seem, in nearby Rotterdam early next morning.

Yet does his invention even matter? After all, dull, still winter afternoons don’t offer the descriptive writer much to go on, and deluge and tempest were just right for his dramatic opening. If he had stuck to the truth, we wouldn’t have had such wonderful passages as: “The Monument, descried through veils of rain, seemed so convincingly liquefied out of the perpendicular that the tilting thoroughfare might have been forty fathoms down.”