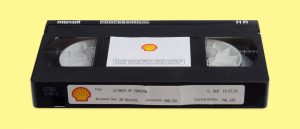

In 2017 Dutch independent news site The Correspondent published a forgotten public information film by Shell made in 1991 in which the oil major warned of the dangers of climate change and the need for urgent action.

(This is an edited version of a piece I first wrote in March 2017.)

In 1991 Shell, yes Shell, warned of “extreme weather, floods, famines and climate refugees as fossil fuel burning warmed the world.”

This is a line in Climate of Concern, a 28-minute film Shell made to be screened to the public, and especially to be viewed by schools and universities. According to Shell the climate was changing “at a rate faster than at any time since the end of the ice age – change too fast perhaps for life to adapt, without severe dislocation. Action now is seen as the only safe insurance.”

In 1991 global warming and subsequent climate change were relatively new concepts, although Shell was not the first internationally known name to flag them up.

In a speech to the United Nations General Assembly on Nov 8 1989, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher acknowledged the looming crisis. “What we are now doing to the world, by degrading the land surfaces, by polluting the waters and by adding greenhouse gases to the air at an unprecedented rate—all this is new in the experience of the earth. It is mankind and his activities which are changing the environment of our planet in damaging and dangerous ways.”

While accepting the uncertainties in computer predictions at the time, Shell’s film noted the various scenarios had “each prompted the same serious warning, a warning endorsed by a uniquely broad consensus of scientists in their report to the United Nations at the end of 1990.

“Global warming is not yet certain, but many think that to wait for final proof would be irresponsible. Action now is seen as the only safe insurance. If the weather machine were to be wound up to such new levels of energy, no country would remain unaffected”.

The BBC, to give it credit, also showed early concern about global warming. I wrote this in 1989, when the BBC prepared an urgent 90 minute documentary on the subject.

We now know that Shell’s film, unearthed by Dutch news website The Correspondent was right about the development and impact of climate change. Prof Tom Wigley, head of the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia when it helped the oil company with the film, told The Guardian the predictions for temperature and sea level rises it made were “pretty good compared with current understanding”.

Thereafter Shell shelved those early warnings, and reverted to “business as usual” mode. Together with other oil companies and the media, with some honourable exceptions, it lobbied against strong climate legislation and, with dangerous complacency foretold a much rosier future.

The issue slipped down the news schedules. The oil industry successfully persuaded governments to continue to grant it tax breaks to help them prospect for and exploit reserves.

Oil and the internal combustion engine continued to be so dominant that it was a further 19 years (2010) before the first all-electric car, the Nissan Leaf, was launched, and even today electric cars make up only a minority of vehicles on the road in the UK.