Watch a prime-time drama on ITV on a Sunday evening and it will be crammed with car adverts. We are offered a pleasurable experience with friends and family in comfortable seats, supported by vaguely useful in-car gadgets and, always, the promise of the open road.

It’s flannel and fluff, and we all know it. We are given nothing but a fuzzy “These are the good times” message. The low and middle range cars are largely interchangeable, and even at the top end they are only offering us minutely different degrees of luxury. Nothing about safety, or the environment or negotiating busy traffic.

It is as if in the early 2000s conventional landline telephone manufacturers had spent millions promoting stylishly upgraded versions of the standard 100 year old telephone, just before the arrival of the iPhone in 2007.

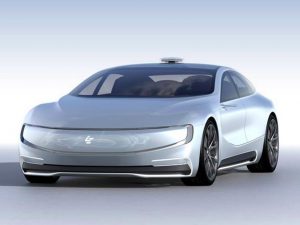

Car adverts, with just a few exceptions, do not mention two of the most important developments in automotive technology today. One is all-electric propulsion. The second is a totally-disruptive driving experience, where the car drives itself.

All these glossy but vacuous commercials are the last, lucrative gasp of one of the most familiar messages in advertising. Within 10 years this familiar, century-old conversation we’ve been having with car manufacturers could be over, to be replaced with something we can scarcely imagine.

According to professional services company KPMG many of us will not even want to own a car 10 years from now. Many of us will share, or call up, a self-driving “robot” car, which may very well be electric, when we need it. The long-predicted motoring revolution could finally be upon us.

Commenting on the findings in its Global Automotive Executive Survey 2017, John Leech, head of automotive at KPMG, said: ”almost the whole automotive industry believes that the mass adoption of electric cars will happen during the next decade”.

And many cars will be driving themselves. Leech added: “I believe robot taxis will revolutionise UK urban transportation in the second half of the next decade.” He said he believed the U.K. with its compact urban areas, was particularly well suited to the early adoption of self driving cars.

Remember, this isn’t vague speculation by ordinary members of the public. The respondents here are all senior people in motor manufacturing.

74% of them told KPMG they expected that more than half of today’s car owners would not own a vehicle by 2025. That implies a massive take-up of self-driving, autonomous cars by only eight years from now. Such remarkable advances are indeed possible if the technology is in place. Just look at the progress in solar power electricity generation in the past six years.

Many new cars are likely to be electric-powered by 2025. 93% of those car industry executives said they were planning to invest in battery electric vehicles by the early 2020s. And 62% of respondents said they believed diesel technology was on its way out.

The prospect of such profound change in the culture of driving, and the disruptive potential of the electric, and the self-driving car, must surprise even those who have followed the sector over recent years.

It must be harder still for the general public to grasp, when their views of been largely moulded by TV series in which the electric car has either been mocked, projected as the tree-huggers’s comfort blanket, and certainly not treated with the seriousness that it deserved.

If the change is going to be as rapid as projected, councils and other public bodies will have to build it into their plans for the quite near future. What is the point of councils planning by-passes and road relief schemes for the 2020s, when the urban traffic levels they are calculating, using existing models, might well be subject to considerable change?

Just consider the benefits of the self-driving vehicle. I live in a large village about 9 miles from the nearest town. There is a regular bus service, but it’s not direct and the mainly-old vehicles are rather shabby. Most people I know never use the bus, and put up with the expense of running two cars. When they arrive in the town, roads are often congested, depending on the time of day. and parking is difficult.

Imagine if a dozen or so self-drive cars were parked in my village. I could call one up; it would arrive on my doorstep in about five minutes and take me to my town, or elsewhere, for much less than the daily cost of owning and providing fuel for a conventional car. At the other end I would be spared the chore of parking, after probably having encountered less congestion on the way.

It is a compelling business model, and even if it has to be refined over time, and with technology constantly improving, it is hard to see what can hold it back.

Several questions arise. We are well aware of powerful industries countering disruptive innovation to protect their interests. Why should motor manufacturers accept a future where we buy fewer cars? And how would they make up the shortfall, as their sales inevitably fall?

The executives questioned in the KPMG survey believe their companies would in the future shift towards generating higher revenues by providing new digital services such as “remote vehicle monitoring”. This will need definition, but, according to the survey “more than three out of four executives believe that one connected car can generate higher revenues [than] the entire life-cycle of 10 non-connected cars [today’s conventional vehicles].”

www.mckinsey.com define the connected car as “a vehicle able to optimize its own operation and maintenance as well as the convenience and comfort of passengers using onboard sensors and Internet connectivity”.

McKinsey estimates that the increase in vehicle connectivity will raise the value of the global market for connectivity components and services to €170 billion by 2020 from just €30 billion [2014 figures].