53 years today, on Saturday, August 31st, 1968, Garfield Sobers became the first player in the history of cricket to hit every ball of an over for six. I was there and I wrote a book about it, Sobers six hit perfection at Swansea: That was the Day.

53 years today, on Saturday, August 31st, 1968, Garfield Sobers became the first player in the history of cricket to hit every ball of an over for six. I was there and I wrote a book about it, Sobers six hit perfection at Swansea: That was the Day.

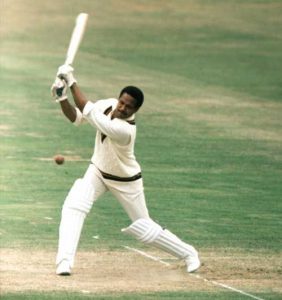

Sobers was captaining Nottinghamshire that day, in a county game against Glamorgan. His feat, which no other batsman had achieved in the 200 years or so cricket had been played, came without warning in Notts’s first innings. It wasn’t part of a frantic run chase, or contrived concession by the other side leading to a declaration. It’s a measure of this achievement by Sobers, generally accepted to have been the greatest all-round cricketer, that it has only been emulated a few times since, and then mainly in the shortened form of the game, where mighty hitting is expected, and even demanded by the crowd.

Glamorgan captain Tony Lewis said afterwards: “It was not sheer slogging through strength, but scientific hitting with every movement working in harmony.”

This is the final extract from my e-book, telling the story of that afternoon, the setting and the events around it – available on Amazon.

______________________________________________

Swansea – August 31st, 1968.

The season was coming to a close. Both sides needed to win that match.

Glamorgan were second to Yorkshire in the Championship, Nottinghamshire were fifth. Victory would lift them one place, and win captain Sobers, a cheerful gambler, a bet and a two bottles of champagne. Bunty Ames, wife of cricketer Les Ames, wagered him Notts would not finish in the top six. They would finish fourth if they beat Glamorgan.

“We were tired and jaded,” said Glamorgan captain Tony Lewis in his 1985 book Playing Days: An Autobiography. “The highest hopes were dead. Yorkshire were already safe at the top.” He describes a “furious” Sobers coming in to bat, annoyed that his batsmen had wasted time. “A benign Sobers is not an animal to taunt, and a mad one is a species to be avoided.”

He explains [bowler] Malcolm Nash’s change of action that day. “Normally he bowled medium fast swing, left arm over the wicket. However Malcolm had noticed that a young man called Underwood had burst into the cricket scene and into the test side with a load of wickets bowling left arm spinners at Malcolm’s [normal] speed. So on this fateful day it was the left arm, around the wicket, Underwood lookalike, who bowled to the angry Sobers.”

Nottinghamshire had earlier won the toss and batted. They made fair progress. But at 308 for 5 Sobers needed quick runs so that he could declare and give his bowlers the chance to attack the Glamorgan top order before close of play.

In My Autobiography (Headline, 2002) Sobers writes that with his score on 40, and with an hour to go, “I thought I should go for it.” He maintained that at this time the object was quick runs. “I wasn’t even bothered if I stayed in or not.”

As Nash prepared to run in to bowl his experimental slow-left armers, the left-handed Sobers studied the field again from the Mumbles Road end, with the sea behind him. At the other (non-striker’s) wicket was Sobers’ fellow batsman, John Parkin.

Sobers already knew the boundaries were not so far away, and the “fairly small boundary on the right hand, Gorse Lane side of the ground, with Malcolm being a left-arm spinner not turning a lot, presented a perfect target.”

Nash ran in off his short run. With the minimum of backlift Sobers punched him over mid-on for six, out of the ground. The crowd murmured. “

Second ball. Almost identical stroke. Sobers struck it high over mid-on, straight to the Cricketers Inn just outside the ground, where Dylan Thomas set one of his short stories.

In came Nash for his third delivery, pushing the ball wider to the off. Another triumph for awesome technique over brute force. Sobers hit him back, straighter over wide mid on, into the pavilion enclosure, lifting his right leg off the ground as he connected.

By now we knew that something rare, if not yet exceptional, was happening. But even if it ended now, this would be a memorable little cameo in a drab summer. It would at least prompt this question: ”Do you remember that time Sobers hit three straight sixes at Swansea?”

Captain Lewis strolled over to Nash and asked him if he wanted to revert to his usual style and “whack it in the blockhole”, then that was fine by him. Nash reportedly replied: “I can handle it. Leave him to me.”

In Taking Fresh Guard, Lewis writes this: “Malcolm had entered the dangerous area where pride moves in, but on rubber legs.”

Why did Nash persevere with his slow-left armers? Because he believed he was bowling balls good enough to get out a lesser batsmen, and to tempt even this colossus to miss-time and give a catch in the deep.

Fourth ball. There Nash was again, off his six step runup. The delivery was straighter. With the speed of lightning, Sobers pulled the ball over backward square leg and over the mid-wicket boundary into the terrace where we were sitting. It rebounded off the concrete terracing and shot back towards the square-leg umpire. Sobers said later that only then did he contemplate going for the six sixes.

Is there a name for the condition in the sports fan where you actually will your opponents to do well, provided he does it gloriously? It does not appear to exist in German, which gave us schadenfreude, a delight in the other’s misfortune. I found something that might come close, the Buddhist concept of mudita. It means “sympathetic or vicarious joy” or “happiness in another’s good fortune”, cited as an example of the opposite of schadenfreude. One definition is “delighting in other people’s well-being rather than begrudging it. [But] the person feeling mudita must not have any interest or direct benefit from the accomplishments of the other.” I think that summed up the feeling of the crowd that distant Saturday.

So it was Nash to Sobers again, straight and pitched up.

Sobers struck the bowler back over his head. But something was very wrong. “It was wide of the off,” he wrote, “and although I caught it well I didn’t middle it.” This ball was flying lower and slower than the last four. Roger Davis, on the long-off boundary, jumped and took the catch. But he was still moving in reverse, back-pedalling. He couldn’t prevent himself from falling backwards. He came to ground over the rope.

Now it was time for confusion and deliberation. Sobers started walking to the pavilion, thinking he had been caught. Davis’s shrug suggested he did not know if the catch would be allowed. There were no big screens in those days. Besides, the technology of the day could not have coped with replays.

Tony Cordle, the fielder nearest to Davis, indicated that it was a six. The two white-coated umpires, Eddie Phillipson and John Langridge, moved together at an unhurried pace, converged and consulted. According to the then experimental change to Law 35, “the fieldsman must have no part of his body grounded outside the playing area in the act of making the catch and afterwards.” Without that change, which seems logical, because the ball still crosses the boundary rope, even if a player is clinging on to it, Sobers would have been out.

As Davis had carried the ball over the boundary, Phillipson signalled another six. For the first time the ground erupted. We didn’t want this to end.

However, in giving the other side a chance, Sobers had revealed himself as the fallible hero. That mistake had evened things up. So there was never any certainty about the last ball. Indeed, the vast weight of cricket history, accumulated in so many dusty volumes, now bore down on Sobers, to say: “It won’t happen”. The story of so many matches, where so many thousands of batsmen have played out so many thousands, even millions, of overs. The odds against this ball going for six too were astronomical.

Captain Tony Lewis sent all his fielders to the boundary, most of them on Sobers’ leg side. Glamorgan wicket-keeper Eifion Jones is said to have challenged Sobers: “Bet you can’t hit this one for six as well.” In ran Nash. All he had to do was put it on a spot where Sobers couldn’t hit it, or at least pitch it up so he couldn’t unleash that deadly swing.

If only it was as easy to keep yourself out of the history books in the presence of greatness. For the first time in the over Sobers seemed to be really trying.

He writes in his autobiography: ”All sorts of things were going through my mind. If he bowled a no ball or wide, that would make it difficult because it would require a seventh ball. [It would not then be six off six. The achievement would have been diluted.] I felt sure he would try to deceive me, [he] being a former fast bowler I thought he would run up as if to bowl another off-break and then bowl a straight, faster ball.

“He didn’t realise we were both thinking along the same lines, and he pitched his quicker ball a little short. I had one eye on the ball, and the other on that short boundary.”

In a microsecond his brain had processed the delivery, and the instant it bounced his bat was describing a glorious arc over his right shoulder. If they ever recreate the over in a movie, the director must not slow this sequence down. The drama is the speed. In a heartbeat, the ball was above our heads and over the boundary, still rising.

“Even if I had a top edge it would have have gone for six, but I caught it right in the middle of the bat and not only did it clear the short boundary, but it went over the stand as well, running down the hill towards Swansea town centre.” We will forgive him the geographical exaggeration – and there is no hill.

“All the way to Swansea,” echoed Wilf Wooller (more understandable excess) in his television commentary. In another sense, though, the ball went further still. Right around the world.

It was the strangest sort of excitement. Not the elation of victory, but the murmured “Did you see that?” after you have witnessed something rare and tremendous. I remember feeling very privileged, that in that instant there was nowhere in the world I would rather have been.

All around there was a murmuring of incredulity, then the sort of warm but restrained applause we wouldn’t recognise today. Pictures show about a quarter of the crowd on their feet, the rest clapping where they sat.

We had just seen the ultimate episode of hitting in the history of cricket. What bearing did Nash’s switch of style have on the outcome of that over we will never know. But listen to John Arlott: “When he was on the kill it was all but impossible to bowl to him. He was one of the most thrilling of all batsmen to watch.”

Glamorgan captain Tony Lewis concurred: “It was not sheer slogging through strength, but scientific hitting with every movement working in harmony.” In the BBC commentary box all the formidable Wooller could manage was: “My goodness gracious, what a moment, what a batsman.”

Sobers could not possibly follow that, and he did not even try. He immediately declared the innings closed and led the players off the field.